James, a pope-like king, proved more determined to found a colony in the New World than Elizabeth had been. In 1606, he issued a charter, granting to a body of men permission to settle on “that parte of America commonly called Virginia,” land that he claimed as his property, since, as the charter explained, these lands were “not now actually possessed by any Christian Prince or People” and the natives “live in Darkness,” meaning that they did not know Christ.

Unlike the Spanish, who set out to conquer, the English were determined to settle, which is why they at first traded with Powhatan, instead of warring with him. James granted to the colony’s settlers the right to “dig, mine, and search for all Manner of Mines of Gold, Silver, and Copper,” the very kind of initiatives taken by Spain, but he also urged them to convert the natives to Christianity, on the ground that, “in propagating of Christian Religion to such People,” the English and Scottish might “in time bring the Infidels and Savages, living in those parts, to human Civility, and to a settled and quiet Government.” They proposed, he insisted, to bring not tyranny but liberty.

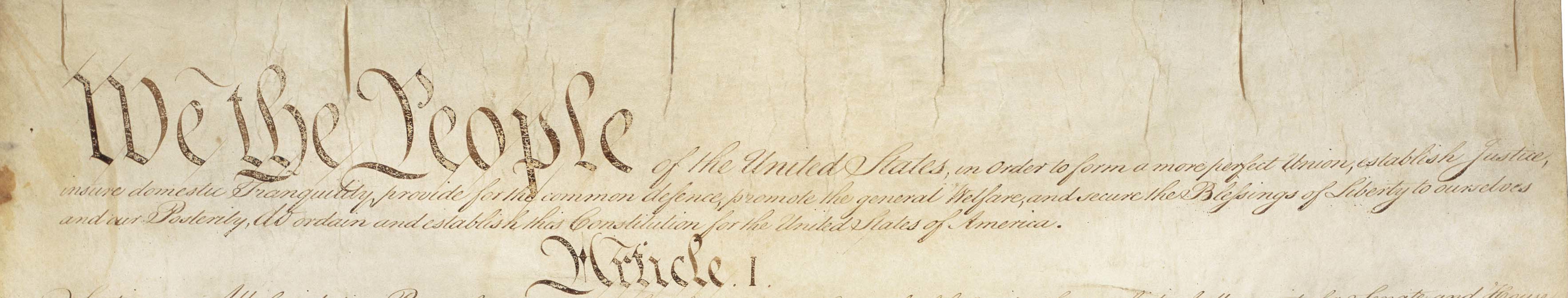

James's charter, like Powhatan’s deerskin, is also a kind of map. (“Charter” has the same Latin root as “chart,” meaning a map.) By his charter, James granted land to two corporations, the Virginia Company and the Plymouth Company: “Wee woulde vouchsafe unto them our licence to make habitacion, plantacion and to deduce a colonie . . . at any Place upon the said-Coast of Virginia or America, where they shall think fit and convenient.”> Virginia, at the time, stretched from what is now South Carolina to Canada: all of this, England claimed.

England’s empire would have a different character than that of either Spain or France. Catholics could make converts by the act of baptism, but Protestants were supposed to teach converts to read the Bible; that meant permanent settlements, families, communities, schools, and churches. Also, England’s empire would be maritime—its navy was its greatest strength. It would be commercial. And, of greatest significance for the course of the nation that would grow out of those settlements, its colonists would be free men, not vassals, guaranteed their “English liberties.”©

At such a great distance from their king, James’s colonists would remain his subjects but they would rule themselves. His 1606 charter decreed that the king would appoint a thirteen-man council in England to oversee the colonies, but, as for local affairs, the settlers would establish their own thirteen-man council to “govern and order all Matters and Causes.” And, most importantly, the colonists would retain all of their rights as English subjects, as if they had never left England. If the king meant his guarantee of the colonists’ English liberties, privileges, and immunities as liberties, privileges, and immunities due to them if they were to return to England, the colonists would come to understand them as guaranteed in the colonies, a freedom attached to their very selves.

[See These Truths pg32-3]

VIRGINIA’ FIRST CHARTER was prepared in the office of Attorney General Edward Coke, a sour-tempered. man with a pointed chin, a systematic mind, and an ungovernable tongue. Coke, who invested in the Virginia Company, was the leading theorist of English common law, the body of unwritten law established by centuries of custom and cases,

.....

In 1603, after James threw Sir Walter Ralegh in the Tower of London, Coke prosecuted Ralegh for treason, for plotting against the king. “Thou viper,” Coke said to Ralegh in court, “thou hast an English face, but a Spanish heart.” Ralegh languished in prison for thirteen years, writing his history of the world, before he was beheaded. Meanwhile, his conviction freed the right to settle Virginia—a right Elizabeth had granted to Ralegh—to be newly issued by James, under Coke’s watchful eye. Two months after issuing the colony’s charter, James appointed Coke chief justice of the court of common pleas.

To settle the new colony, the Virginia Company rounded up men who were eager to make their own fortunes, along with soldiers who'd fought in England's religious wars against Catholics and Muslims. Burly and fearless John Smith, all of twenty-six, had already fought the Spanish in France and in the Netherlands and, with the Austrian army, had battled the Turks in Hungary. Captured by Muslims, he’d been sold into slavery, from which he’d eventually escaped

....

Whatever “quiet government” the company’s merchants had intended, the colonists proved ungovernable. They built a fort and began looking for gold. But a band of soldiers and gentlemen- adventurers proved unwilling to clear fields or plant and harvest crops; instead, they stole food from Powhatan’s people, stores of corn and beans. Smith, disgusted, complained that the company had sent hardly any but the most useless of settlers. He counted one carpenter, two blacksmiths, and a flock of footmen, and wrote the rest off as “Gentlemen, Tradesmen, Servingmen, libertines, and such like, ten times more fit to spoyle a Commonwealth, than either begin one, or but helpe to maintaine one.”!

In 1608, Smith, elected the colony's governor, made a rule: “he who does not worke, shall not eat.”

....

And still the English starved, and still they raided native villages. In the fall of 1609, the colonists revolted—auguring so many revolts to come—and sent Smith back to England, declaring that he had made Virginia, under his leadership, “a misery, a ruine, a death, a hell.”

....

In the winter of 1609-10, five hundred colonists, having failed to farm or fish or hunt and having succeeded at little except making their neighbors into enemies, were reduced to sixty.

....

In 1622, four years after Powhatan’s death, the natives rose up in rebellion and tried to oust the English from their land, killing hundreds of new immigrants in what the English called the “Virginia massacre.” Hobbes, working out a theory of the origins of civil society by deducing an original state of nature, pondered the violence in Virginia. “The savage people in many places of America... have no government at all, and live at this day in that brutish manner,” he would later write, in The Leviathan, a treatise in which he concluded that the state of nature is a state of war, “of every man against every man.”

Miraculously, the colony recovered; its population grew and its economy thrived with a new crop, tobacco, a plant found only in the New World and long cultivated by the natives.24 With tobacco came the prospect of profit, and a new political and economic order: the colonists would rule themselves and they would rule over others. In July 1619, twenty-two English colonists, two men from each of eleven parts of the colony, met in a legislative body, the House of Burgesses, the first self-governing body in the colonies. One month later, twenty Africans arrived in Virginia, the first slaves in British America, Kimbundu speakers from the kingdom of Ndongo. Captured in raids ordered by the governor of Angola, they had been marched to the coast and boarded the Sao Jodo Bautista, a Portuguese slave ship headed for New Spain. At sea, an English privateer, the White Lion, sailing from New Netherlands, attacked the Sdo Jodo Bautista, seized all twenty, and brought them to Virginia to be sold.

Twenty Englishmen were elected to the House of Burgesses. Twenty Africans were condemned to the house of bondage. Another chapter opened in the American book of genesis: liberty and slavery became the American Abel and Cain.

[see These Truths pages 34-8]