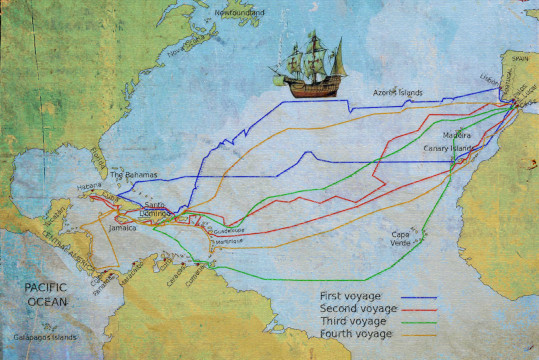

George Bancroft published his History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent to the Present in 1834, when the nation was barely more than a half- century old, a fledgling, just hatched. By beginning with Columbus, [map from The Wild Life of Columbus] Bancroft made the United States nearly three centuries older than it was, a many-feathered old bird. Bancroft wasn’t only a historian; he was also a politician: he served in the administrations of three U.S. presidents, including as secretary of war during the age of American expansion. He believed in manifest destiny, the idea that the United States was fated to cross the continent, from east to west. For Bancroft, the nation’s fate was all but sealed the day Columbus set sail. By giving Americans a more ancient past, he hoped to make America’s founding appear inevitable and its growth inexorable, God-ordained. He also wanted to celebrate the United States, not as an offshoot of England, but instead as a pluralist and cosmopolitan nation, with ancestors all over the world. “France contributed to its independence,” he observed, “the origin of the language we speak carries us to India; our religion is from Palestine; of the hymns sung in our churches, some were first heard in Italy, some in the deserts of Arabia, some on the banks of the Euphrates; our arts come from Greece; our jurisprudence from Rome."

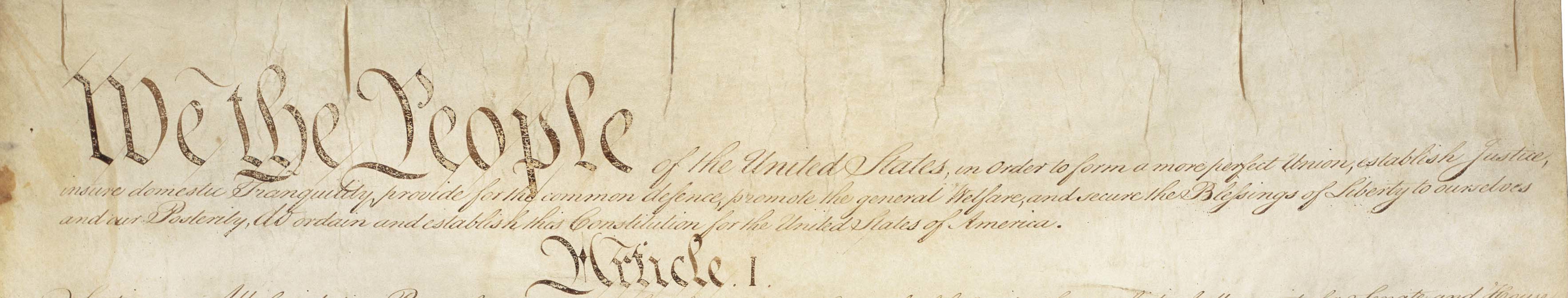

[See These Truths, pg10]

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era, also known as the pre-contact era , or as the pre-Cabraline era specifically in Brazil, spans from the initial peopling of the Americas in the Upper Paleolithic to the onset of European colonization, which began with Christopher Columbus's voyage in 1492. This era encompasses the history of Indigenous cultures prior to significant European influence, which in some cases did not occur until decades or even centuries after Columbus's arrival.