1783-1815: Library of Congress

At the successful conclusion of the Revolutionary War with Great Britain in 1783, an American could look back and reflect on the truly revolutionary events that had occurred in the preceding three decades. In that period American colonists had first helped the British win a global struggle with France. Soon, however, troubles surfaced as Britain began to assert tighter control of its North American colonies. Eventually, these troubles led to a struggle in which American colonists severed their colonial ties with Great Britain. Meanwhile, Americans began to experiment with new forms of self-government. This movement occurred in both the Continental Congress during the Revolution and at the local and state levels.

See The Confederation Period, from Wikipedia:

The Confederation period was the era of the United States' history in the 1780s after the American Revolution and prior to the ratification of the United States Constitution. In 1781, the United States ratified the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union and prevailed in the Battle of Yorktown, the last major land battle between British and American Continental forces in the American Revolutionary War. American independence was confirmed with the 1783 signing of the Treaty of Paris. The fledgling United States faced several challenges, many of which stemmed from the lack of an effective central government and unified political culture. The period ended in 1789 following the ratification of the United States Constitution, which established a new, more effective, federal government.

See The Constitutional Convention

From These Truths:

The confederation limped along, weak and hobbled. France and Holland pressed for payment of debts—in real money, not the paper promises on which the Republic floated. “Not worth a continental,” a phrase used to describe the paper currency printed by Congress, entered the lexicon. Congress was unable to pay its creditors and, by 1786, the continental government was nearly bankrupt. The states, too, were in distress; they could levy taxes, but they couldn't reliably collect them. Massachusetts had levied taxes to retire the state’s war debt; farmers who failed to pay could have their property seized and auctioned. Many of those farmers had fought in the war, and, beginning in August 1786, they decided to fight again: well over a thousand armed farmers in western Massachusetts, angry and alienated and led by a veteran named Daniel Shays, protested the government, blockading courthouses and seizing a federal armory.

It seemed as if the infant nation might descend into civil war, beginning an unending cycle of revolution. “I wish our Poor Distracted State would atend to the many good Lessons” of history, Jane Franklin wrote to her brother, and not “keep always in a Flame.” Madison feared the rebellion would spread all the way to Virginia. Washington began to wonder whether the nation needed a king after all, writing to Madison, “We are fast verging to anarchy and confusion!” As Madison reported to Jefferson, Shays’s Rebellion had “tainted the faith” of even the most committed republicans.

... (pg 115-6)

See The Federalist Era, from Wikipedia:

The Federalist Era in American history ran from 1788 to 1800, a time when the Federalist Party and its predecessors were dominant in American politics. During this period, Federalists generally controlled Congress and enjoyed the support of President George Washington and President John Adams. The era saw the creation of a new, stronger federal government under the United States Constitution, a deepening of support for nationalism, and diminished fears of tyranny by a central government. The era began with the ratification of the United States Constitution and ended with the Democratic-Republican Party's victory in the 1800 elections.

Washington's Deification, from These Truths, pages 148-9:

At George Washington's death, the nation fell into mourning, in a torrent of passion. People preached and prayed; they dressed in black and wept. Shops were closed. Funeral orations were delivered. “Mourn, O, Columbia!” declared a newspaper in Baltimore. The Farewell Address was printed and reprinted, read and reread, stitched, even, into pillows.

“Let it be written in characters of gold and hung up in every house,” one edition of the Address urged. “Let it be engraven on tables of brass and marble and, like the sacred Law of Moses, be placed in every Church and Hall and Senate Chamber.”

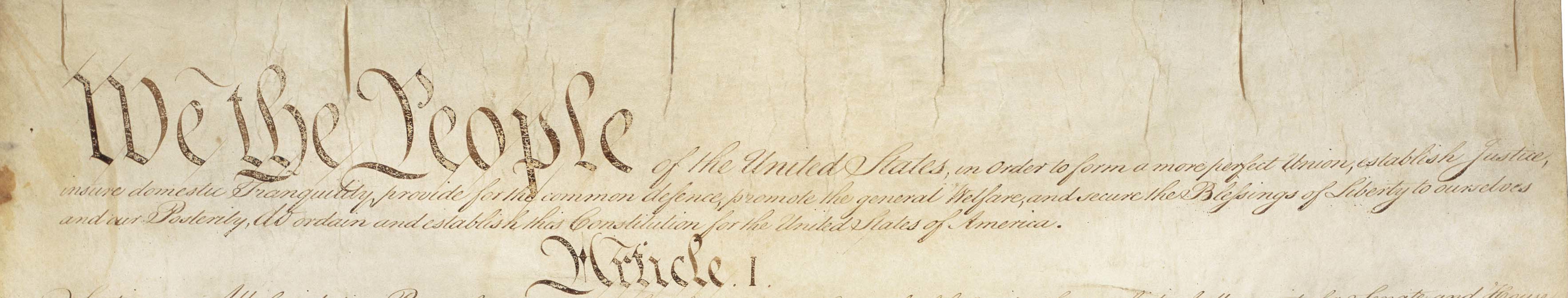

Let it be written. Americans read their Washington. And they looked at him, in prints and portraits. One popular print, Washington Giving the Laws to America, showed the archangel Gabriel in the heavens carrying an American emblem while Washington, dressed in a Roman toga and seated among the gods, holds a stylus in one hand and, in his other hand, a stone tablet engraved with the words, “The American Constitution.” It was as if the Constitution had been handed down from the heavens, tablets etched out of stone, sacred and infallible, from God to the first American president. Where were the centuries of ideas and decades of struggle? What of the hardscrabble American people and their fiercely fought debates? What of the near fisticuffs over ratification? What of the feuds and the failures and the compromises, the trials of facts, the battles between reason and passion?

In the quiet of a room in a house not too far away, James Madison pulled out of a cabinet the notes he had taken down, day after day, at the constitutional convention, that sweltering summer in Philadelphia. He read over them and wondered at them, and then he settled to the work of revision, word by word. He puttered away, in secret, page after page. In his desk, he kept safe, for another day, the story of how the Constitution had been written, and of its fateful compromises.